Public outcry over a proposed 17-ft wall and other physical barriers to prevent storm surge along the Texas coast has led the Army Corps of Engineers to switch gears. Now, the Corps will focus on more nature-based solutions such as beaches and sand dune systems.

In October, the Corps and Texas General Land Office released the Coastal Texas Protection and Restoration Study Draft Integrated Feasibility Report, which outlined approximately $32 billion in projects with multiple lines of defense to improve the resiliency of the Texas coast to future storm events.

In that plan, the Corps proposed building a 17-ft-tall barrier going down the center of Bolivar Peninsula, as well as a barrier on the west end of Galveston Island, says Kelly Burks-Copes, a research ecologist at the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center and project manager on the study.

During the 105-day public review period following the report’s release, the Corps received about 13,000 comments, with many against the barrier plan.

This led the Corps to drop plans for the barrier down the center of Bolivar and Galveston, and “instead, we are proposing a different kind of nature-based feature—a beach and dune system along the front of those two barrier islands,” says Burks-Copes. “So it will provide and afford not only the risk reduction, but also ecosystem habitats for different species.”

New plans call for a continuous line of dunes between 8 ft and 13 ft high, with cuts for drainage and beach access, spanning the more than 60-mile-stretch along Bolivar Peninsula and Galveston Island. Vegetation atop the dunes would help solidify their shape.

“We would be adding material at the vegetative line, and then towards the ocean there would be a dune, and out in front would be a berm, then there would be a drop off into the water,” she says.

Researchers are currently working through a life-cycle analysis to determine how often the sand would need to be replenished. Since the decision to switch to the beach and sand dune system was made within the last month, cost estimates are still forthcoming.

“There are some things to be cognizant of in terms of species requirements. With sea turtles, the color of sand affects whether the eggs mature into females or males, so we have to be very careful about the materials that we use,” says Burks-Copes.

While the Corps is currently evaluating the effectiveness of the natural barriers compared to the originally proposed levees, the Corps expects that there will be greater risk with the nature-based features, but it is still modeling those risks.

Meanwhile, the Texas General Land Office is conducting a series of community workgroups, where elected officials and community representatives are sitting down with land office officials, with Corps experts on hand, to discuss the project as it evolves, says Tony Williams, director of planning, coastal resources at the office.

Meetings have been held for Bolivar, Galveston and Harris County and South Padre Island.

Once the second draft of the Coastal Texas Study is complete in September 2020, the Corps is planning to conduct a second round of public reviews and meetings, with the goal of having the final study ready to go in April 2021.

The Texas Coastal Study will become 100% federally funded starting Oct. 1, 2019.

“Once the study is complete and it goes into preliminary engineering and preconstruction engineering and design, or into construction, it will be 65/35 split federal/non-federal through construction,” Williams says.

When funding is available and ready, the Corps could have all the components of the plan built within 10 years, Burks-Copes says.

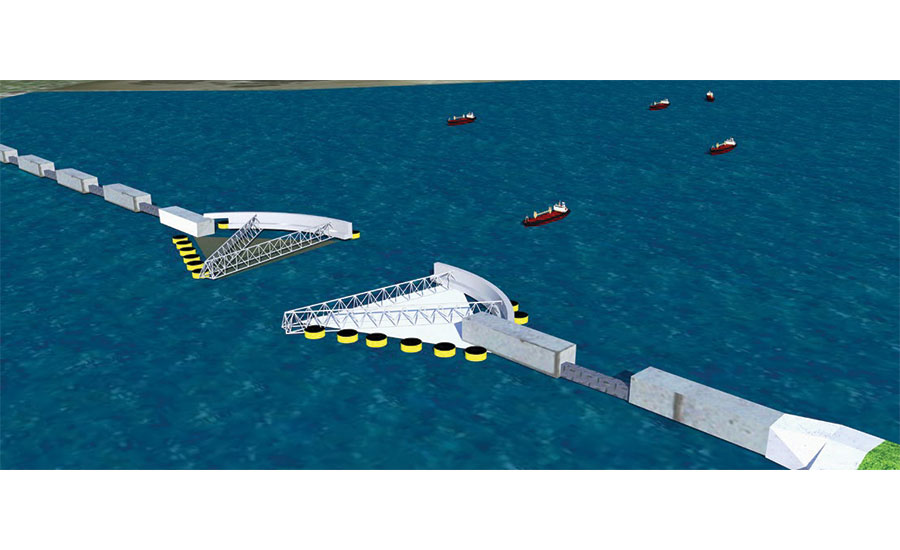

Work is continuing on the proposed storm surge barrier gates between Bolivar Peninsula and Galveston Island as well.

The coastal study team is refining the barrier design, trying to reduce the barriers’ impact on navigation and the environment, Williams says.

“Now they’re getting away from the idea of one huge floating sector gate to having two floating sector gates that would be smaller, but each of those would have one-way traffic,” says Scott Jones, government and regulatory affairs manager at the Galveston Bay Foundation, and participant in the GLO’s workgroups. “Anything that would improve navigation safety is a good thing as long as it doesn’t cause any more constriction of the pass, which is our main concern.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment